By Belinda Griswold

Everyone, welcome and super warm welcome. My name is Belinda Griswold. I use she/her pronouns, I live on Snohomish land in Skagit land in western Washington. I’ve facilitated the Work That Reconnects for many years and been particularly interested in the Work that acts as a movement tool and as a tool of undoing oppression with other movements and communities… I do a lot of work with historically white-led organizations on racial justice and other types of transformation within organizations related to equity and justice. [Belinda asks all in the room to introduce themselves and say where they are from.]

People living in different cultural contexts have extremely different experiences of oppression, domination, and liberation.

I’m going to share a very simple kind of schema that I put together based on the work of a lot of people over many years, including my dear friends Carmen [Rumbaut] and Constance [Washburn], and many others who have worked to bring and to elevate awareness of oppressive dynamics and cultural appropriation in the Work That Reconnects. As facilitators of the Work That Reconnects, we can bring rigor to our facilitation practice, and that’s good.

What I’m learning is that some of the most fundamental best practices fit into these three categories: accountability, learning, and courage. There are many ways to talk about all of these learnings and resources

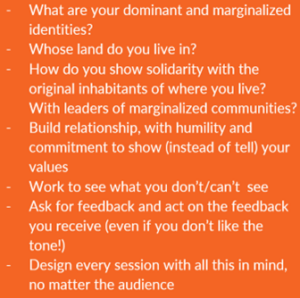

Accountability

What do I mean when I say accountability? For facilitators of the Work That Reconnects it, it has a particular meaning. A lot of it is about understanding our own social location, privileged and marginalized identities in our particular context, where we are living if we’re living in colonized land. If the land we’re living on is not the land of our ancestors, whose land is it?

How do we show up in solidarity with the people whose land we’re living on? Particularly for those of us who are not living on the land of our ancestors, there’s exploration around accountability with leaders of marginalized communities.

I come at this from the perspective that the Work That Reconnects is an incredible tool for strengthening social movements for the just transition to a life sustaining society. These technologies that Joanna and many others have developed over decades are incredibly powerful tools. However, they’re not necessarily always taught or contextualized that way. So building relationship and having a sense of commitment to our communities that we’re actually living and working in is a pretty fundamental skill, in my opinion, to develop as a facilitator. If we are not engaged in our own communities and [working] for justice in our own communities, it’s difficult to bring that into our facilitation.

A commitment to see what we don’t currently see, or may not be able to see, in terms of power differentials in our communities and in our movements

Another dimension of this relationship building orientation is having a commitment to see what we don’t currently see, or may not be able to see, in terms of power differentials in our communities and in our movements. That’s kind of impossible, right? Like how the hell are you supposed to see what you don’t see? The first thing to do is to know that we might not see, and that can cause us to look in a deeper way, to investigate what kinds of power differentials we might not be able to detect, both in our communities and in the spaces where we’re facilitating.

We’re always asking folks how things are going and what they want and need to share with us as facilitators

So that is a big one. Also, a lot of times people give facilitators feedback that’s hard to hear, They’re mad when they say it, or they or we are defensive, or it’s difficult to hear in some way. And it really is a core capacity of a strong facilitator that even if you don’t like the tone, even if you don’t like the vibe, even if you’re reactive to how it’s delivered, we still listen, and we do our best operationalize and act on that, particularly when the feedback is coming from folks who hold more marginalized identities than we do as facilitators.

And then finally, with regard to accountability, one of the great things about the Work That Reconnects is there’s a lot of heterogeneity [among our participants.]. What I’ve learned is that if we don’t design our sessions with accountability [for that heterogeneity] in mind, we’re going to cause harm, more than we might if we use accountability as a fundamental tool for how we design our Work That Reconnects gatherings. Things go better, people learn more, it’s more supportive, and it’s less harmful. So that’s what I mean by that.

It’s a lot about designing so that we are taking power differentials into account and not … delivering content from one particular social location.

Learning

Let’s talk about learning. Continual learning is a fundamental good practice for facilitators across all sorts of disciplines. It’s particularly important in the Work That Reconnects because the Work That Reconnects came out of a very particular moment, movement, person. And times have changed since the Work That Reconnects came into being in its beautiful way in the 70s.

Although we have all these incredible texts, and practices and community, there’s a real need for ongoing learning by facilitators in particular, I think, around how are people in my community, in my country, talking about equity and justice? And how can I weave that into the Work That Reconnects? I urge all facilitators as kind of an underlying dimension of your work to be engaged in continual learning.

And back to what we talked about a minute ago, in terms of accountability, if we’re constantly asking ourselves, what am I not quite seeing? What might I be missing as a facilitator? That will guide our learning in a way that I have found to be tremendously helpful, to just keep asking myself that question.

It’s an incredibly important skill for facilitators to be able to notice when our nervous systems get ramped up

Also, for those of us who hold a lot of privileged identities, or even just a couple of privileged identities, we’re going to make mistakes when we’re trying to facilitate from a more justice-focused perspective. That’s how it is. And we can actually learn from them.

In some places, maybe more in the US than other places, there’s a tendency to get tight and try to do it all right, and perfectly. And that just never works because making mistakes is human. And making mistakes is particularly common among people who have more social power, because we can’t quite see what we’re doing a lot of the time. So I urge new and emerging facilitators to be like, “Yep, that’s gonna happen.”

Courage

Bravery is being willing to hold an experimental lens, and hold the spaces lightly enough that you can change course

A lot of times in earlier days there was so much loyalty to the methodology and to the spiral that something would happen, and someone would be like, ooh, that felt weird or that felt like that was a micro aggression, or even a macro aggression. And it would be like, “Sorry, we don’t have time for that, because we’re doing the spiral.” This bravery part is really connected to never saying that. In the sense that if people are raising issues, or your belly is telling you, “Hey, there’s something alive here in terms of power dynamics in this room,” then be brave enough to name it. Be brave enough to pause. You don’t have to do it perfectly. Imperfect interruption and pausing is way better than none at all. When we name power and identity differentials, when we see them, and we ask others, like participants and co-facilitators, it creates so much more of a brave space.

I think most folks are working with group commitments these days. And if you’re not, then those are certainly available. When we say affinity groups here, that means allowing folks to gather by identity, so that maybe not everyone is in the same room all the time. And there can be learning and healing and nourishing among marginalized folks and the privileged folks. We [privileged folks] can have our own room for our kind of clumsy learning, and not drag our friends and colleagues with marginalized identities through our learning.

This article is an edited transcription of a talk given at the Gaian Gathering of the Work That Reconnects Network in November 2023. A video of the full talk is available on the WTR Network website here.

Belinda Griswold is a mediator, communications director, attorney, and WTR facilitator specializing in racial justice approaches for a wide variety of organizations and people. She is passionate about building organizational, personal, and community resilience as we push for a just transition in our movements and economies. Belinda lives with her family, pit bull, and pony on Snohomish lands in Western Washington, and has recently been honored to work on Indigenous-led river and salmon campaigns throughout the Pacific Northwest. Learn more about her work here: https://www.resource-media.org/staff/belinda-griswold/

Belinda Griswold is a mediator, communications director, attorney, and WTR facilitator specializing in racial justice approaches for a wide variety of organizations and people. She is passionate about building organizational, personal, and community resilience as we push for a just transition in our movements and economies. Belinda lives with her family, pit bull, and pony on Snohomish lands in Western Washington, and has recently been honored to work on Indigenous-led river and salmon campaigns throughout the Pacific Northwest. Learn more about her work here: https://www.resource-media.org/staff/belinda-griswold/